As players of a fret-less stringed instrument that’s not set to equal (or meantone) temperament like a keyboard or marimba, we have the liberty to utilize more than one tuning system. With multiple tuning systems, there’s no such thing as absolutely perfect intonation. Playing the most in tune we can on the violin (or viola, cello, etc) requires a combination of stellar sense of relative pitch combined with active listening, a stable instrument setup, and a reliable left hand technique. The combination of ear training and physical technique creates the mind-body connection (or ear-finger connection, if that makes more sense to you), which allows us to play in tune consistently.

In this post I refer to the violin for everything, but all the ideas can be applied to other un-fretted stringed instruments. The concepts below are easier to understand through visual and aural demonstration rather than written form, which is why I created the accompanying video for better clarity and examples. Feel free to scroll past the text to skip to the video.

Relative Pitch

Relative pitch is the ability to hear and understand the relationship between notes and harmonic qualities (and their functions). Unlike perfect pitch (the ability to identify a note based on sound alone), which is an innate ability from birth, relative pitch can be trained and developed over time. Some people develop it further than others; much of the development depends on being exposed to a wide palette of music, attentive listening, studying music theory, and being active as a player.

One of the most basic skills in ear training is to recognize whether something is in tune or not; and if it’s out of tune to be able to tell if a note is too sharp or too flat.

Here are a few practice methods to become more consistent with hitting notes in tune on the violin:

Hear Before You Play

To play violin in tune, we have to use our internal ear in such a way that we can “hear” an upcoming pitch in our mind before actually playing it. This is especially useful for moments when there are shifts and big leaps in the music. Use the sense of relative pitch – especially understanding the quality of intervals – to “hear ahead” before the note comes out of the instrument.

Example: Play an A on the G string and shift up to an F# on the same string. To improve the accuracy, first play the A. Then, knowing that F# is a major 6th above, sing a major 6th interval above the A internally (if you’re not sure, play the F# on the D string to check). Perform the shift slowly and let the ear be the guide; the action of the hand follows the ear.

Checking With Open Strings

If you’re playing a piece in a “violin-friendly” key that has notes matching to the open strings (ie – keys of G, D, etc), check perfect intervals of the given key with open strings.

Example: You’re playing a piece in d-minor. Use the open D string as reference for D’s in all octaves. G and A are respectively perfect 4th and perfect 5th above the home key, so they can be checked with the D string as well. You can also check G and A with their respective open strings of the same name. In addition, E’s can be tuned as a perfect interval to the open A.

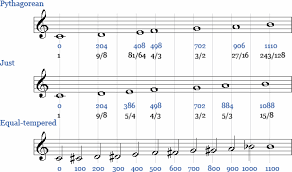

Tuning Systems

Avoid tuning 6ths and 3rds with open strings unless they are part of a double-stop or chord. Doing so when one of these notes is part of a melodic passage (especially if it’s a non-chord tone) will create a switch in tuning systems, causing the note to sound out of tune in relation to the melody. Tuning a 3rd or 6th to the tonic or dominant utilizes the “just” intonation system, which is used primarily to tune chords and double-stops. This is very useful in an ensemble setting, especially when the 3rd of the chord is not in the top voice.

In the previous example in d-minor: tuning an F with open A, or a Bb with open D.

Most of the time, on the violin we utilize the “pythagorean” intonation system for melodic passages. This system is based on perfect 5ths (the interval between each adjacent pair of strings). Its most prominent distinction from just intonation (or equal temperament) is the size of non-perfect intervals from the tonic; they become “too wide” or “too narrow” from the tonic because of the system’s priority to keep all perfect intervals pure. As a result, chords in pythagorean system sound out of tune to the trained ear.

Because there is no “perfect intonation,” we need to make compromises and understand when and why to switch between tuning systems. A musician with a well-trained ear and a great sensitivity to harmonic progression can switch between the systems seamlessly, without consciously thinking about it.