To execute a specific skill, an athlete’s movement goes through 3 phases: the preparation, the action (this can be a tennis serve or golf swing, for example), and the follow-through. String playing is no different when it comes to consistency in the beginnings and ends of our notes. The quality of these prep and follow-through movements will determine the quality of the note(s).

To improve these movements and execute them with better intension, first, we check for relaxation and good balance in our posture. Then, we need to take into account the musical excerpt in question. What type of bow stroke is needed for the phrase in question – is it an energetic martele? Slow legato? Detache? Spiccato? Will the arm, hand, and bow move together in one quick motion (i.e – martele) or will it have a sequential wave-like pattern (i.e. – legato or slow/moderate detache)? Or perhaps it’s a quick cyclic pendulum-like motion (i.e. – sautille).

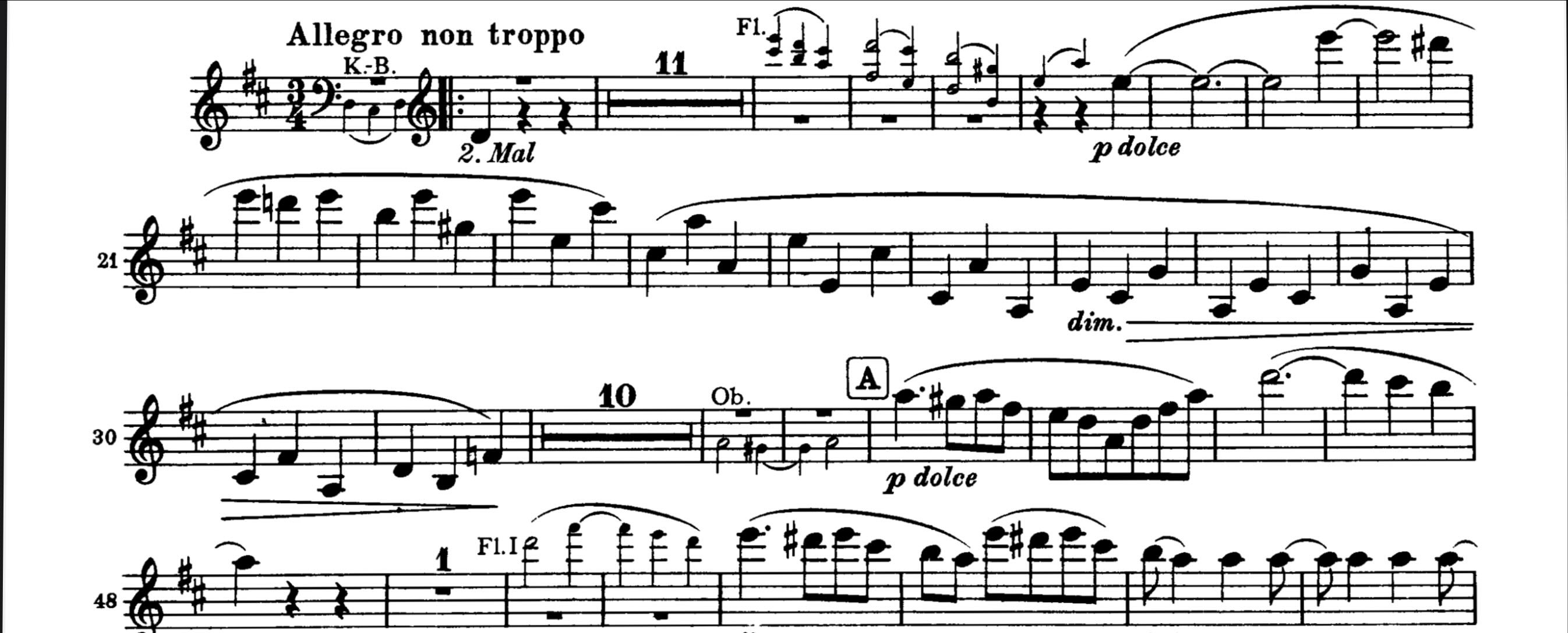

Excerpt Example: Brahms

Usually, the type of motion needed changes throughout a single piece (and sometimes even within the same section). A prime example of this is in the first violin part of Brahms’s 2nd symphony. The first entrance (m. 17) is in the “slow, controlled” category:

Then, at rehearsal E (m. 118), we get the “ballistic” movement on the accented dotted quarter notes and tied notes that follow:

Once the necessary type of movement has been identified, now is a good time to consider unilateral and bilateral motion.

Unilateral Motion

Unilateral motion is when the body transfers weight toward the same direction as the bow. It helps to extend the legato stroke and encourages the upper arm to lead in very slow bows. This is especially helpful in the opening of the Brahms example above, where we can change bow directions as needed. Unilateral motion here will help create a more uniform sound in different parts of the bow. Ironically, to play slow, long bows in a soft dynamic, the bow needs to be held just a little more firmly (but without extra tension) and the motion is directed by the larger muscles (including the shoulder blade).

Preparation for Unilateral Motion in Brahms

In the case of a good preparatory motion for the Brahms, if we were to begin on a downbow, we would need to lean the body, in rhythm, to the left foot before starting the first note. (And if we begin upbow, we need to prepare by having the body’s weight distributed evenly/centered.) Even before the prep, it would be helpful to rock to the pulse of the piece back and forth for a few measures leading up to the entrance. Then during the prep (the first 2 quarter beats of measure 17) the bow would move to the string in the intended character and same speed as it would begin to play the note, as the weight is transferred accordingly.

Bilateral Motion

Bilateral motion is when the bow moves in the opposite direction of the body’s weight transfer. It’s helpful for most other types of bow strokes. Even in fast 16th note passages, the body responds on a more “microscopic” level in

bilateral motion when it’s free of excess tension. Bilateral motion gives the sound more resonance, power, and freedom. This is especially clear in the Brahms example at rehearsal E.

Preparation for Bilateral Motion in Brahms

A good preparatory motion to start Rehearsal E in Brahms 2 is one that matches in character and speed of the first note. Since the bow is in the lower half here (i.e. – balance point or frog), we need our body weight to be centered and even among the two feet. During the dotted 8th + 16th rhythm, the bilateral motion is very small and swift, since we stay in the lower quarter of the bow. However, on the accented dotted quarter (high E), the weight transfers toward the left foot as the hand, arm, and bow all move together.

Follow-Through

Finally, we need to consider the quality of the follow-through.

“In string playing, the movement needs to survive the sound.” (Paul Rolland. The Teaching of Action in String Playing. p. 38).

In the second Brahms excerpt, the quality of the follow-through of the dotted quarter note will decide the quality of the prep and sound for the sforzando upbow (tied C#) that follows. Often times, a follow-through turns into, or IS the new prep motion for what comes next. In the slow Brahms example, the follow-through after measure 31, needs to give the impression that we continue to play, even though the sound passes to another instrument in the orchestra.

Another key for a good prep and follow-through also lies in the presence and timing of counter-balance in bilateral or unilateral motion. This is particularly the case for sequential motions, in which one part of the body

starts a new direction while another part is finishing the previous movement.